By RYAN SOULARD

Michigan Department of Natural Resources

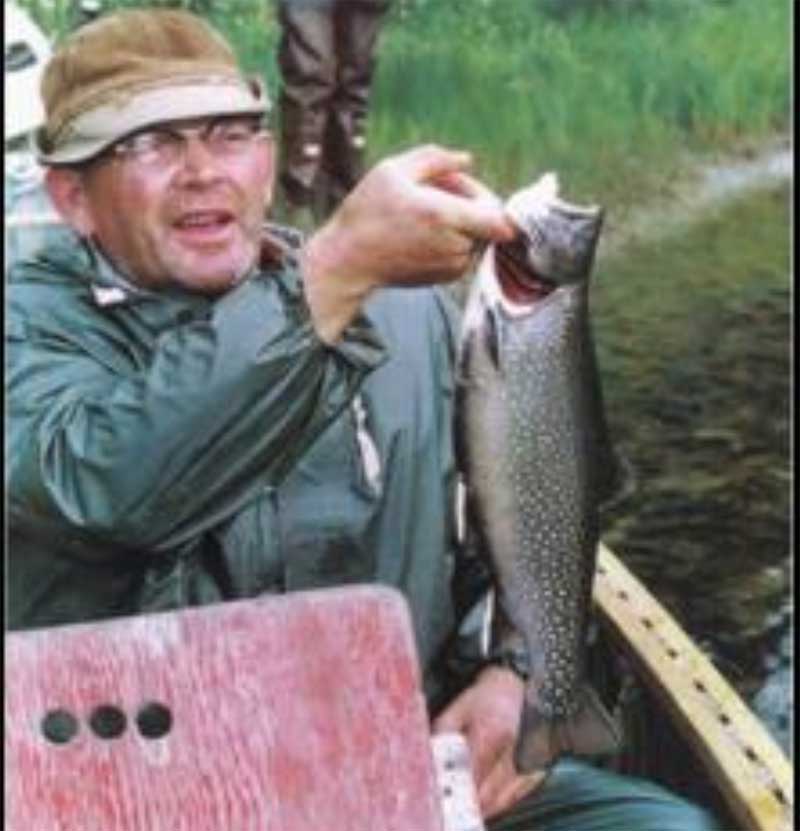

It was a rainy, cool, spring day a few years ago, when my wife and I hit the water with fishing guide Ed McCoy on the Manistee River.

Still in my infancy stage of learning which bugs hatch when, and what flies to match them with, I was eager to soak up everything I could.

My wife, the trooper she always is, had a smile on her face despite the dreary weather. As the old saying goes, “A bad day of fishing, beats a good day at work.”

So off we went.

Soon into the float, it became very apparent that fly fishing in the rain wasn’t a bad thing after all. It seemed like wherever we placed our fly, with the careful guidance of Ed’s rowing skills, brook trout and brown trout were crushing our flies with reckless abandon.

“What fly is this?” I asked Ed.

“Roberts’ Yellow Drake.”

It soon became clear to me that this fly was something I needed to have in my arsenal when I am hitting the waters of northern Michigan. It also occurred to me that these tiny yellow bugs must taste like the finest meal you’ve ever had to a fish, just judging by the constant attention these daytime trout were giving them.

As the days passed following that trip, my mind wandered back to just how great it was.

We don’t own a drift boat, so it was nice to experience the river with a first-class guide leading the way, sharing all his knowledge with us – from insects to casting.

As we stopped for lunch that day and the rain really picked up, I remember holding a small container of pasta salad Ed brought and watching it fill with water as I held it.

I still can taste that little tub of pasta salad and how delicious it was, watered down, probably having some residue off the cedar tree we were parked under, and who knows, maybe even a mayfly or two.

It doesn’t matter what you eat while out fishing, it just tastes 20 times better. Look it up, it’s got to be a rule somewhere.

On that fishing excursion, we had prolific insect hatches of Emphemerella, or sulfurs as they most commonly are known.

One mystery still evaded me as I looked back on this great trip: “Who was Roberts and why does his sulfur imitation work so wonderfully?”

After some internet sleuthing, I was delighted to find a couple of great articles written about Clarence Roberts and his Yellow Drake. What made it even more special to me was finding out that he and I were kindred souls in our career paths.

Roberts had been a game warden (before they were called conservation officers) for the Michigan Department of Conservation (the precursor to the Michigan Department of Natural Resources) and he was obviously a fishing fanatic. As a wildlife biologist for the Michigan DNR, it absolutely made my day to read this.

He was born in 1916 in the little town of Onaway in the northern Lower Peninsula. As the lore surrounding Clarence goes, his “trout madness” all started when his brother Cliff purchased several items from the Herter’s catalog in the 30s and began tying flies.

When Cliff joined the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1942, he needed someone to pass his materials along to, and his brother Clarence was the perfect candidate, living in a hallowed trout fishing area around Grayling and working in the outdoors.

You could say that Clarence dove in head over heels because by 1949, he was commercially tying flies and selling to bait shops, gas stations, hardware stores and canoe liveries.

At the height of his enterprise, Clarence was commercially tying over 5,000 flies a year. He raised his own roosters to use their hackles for fly tying, and he scavenged a road-killed animal or two in his game warden duties for fur to tie with.

Roberts made a big impact regionally and around the Au Sable River, both as a game warden and for his innovations in fly tying.

He is credited as one of the first people to ever tie flies with deer hair parallel to the hook to add buoyancy and help the fly ride better in the water, which is a tenet of fly tying born in Michigan that has since spread globally.

To think that on the backside of World War II, there were people tying flies and making more money than their work salaries!

Enter George Mason and George Griffith.

According to the book “America’s 100 Best Trout Streams” by John Ross, “The idea for Trout Unlimited was hatched at a chance meeting in 1950 of George Griffith, a hosiery salesman, and George Mason, president of American Motors, as both men were waiting to launch their Au Sable riverboats at Burton’s Landing.”

Mason was a Ducks Unlimited member who suggested a similar organization for trout be started.

After Mason died in 1954, Griffith – a member of the Michigan Conservation Commission – and others picked up the flyrod and kept moving the idea forward.

Griffith went on to hold a landmark meeting on the banks of the Au Sable with the likes of Fred Bear, Mort Neff, Al Neuman and several others that led to the creation of Trout Unlimited in 1959, which grew into the international organization we know today.

It is said that somewhere between 1957 and 1959, Clarence Roberts and George Griffith were fishing together when Griffith hooked a log with a streamer fly pattern, tugging it, causing it to rocket loose, injuring his eye and leading to subsequent vision issues.

After that, Roberts began tying the Roberts Yellow Drake with the large white parachute post so that Griffith could more easily see the fly on the water.

I would have loved to be a fly on the water back in the 40s and 50s and listen to the conversations among anglers and what they were brainstorming.

Here they were coming out of some of the darkest moments in history, the Great Depression of the 1930s, then World War II in the 40s and the Cold War of the 1950s.

Yet somehow, these great giants of conservation were able not only to keep a level head but to devise plans on how to save and enhance cold-water fisheries in northern Michigan.

Those foundations have spread globally and have made lasting positive impacts.

I guess I should not be surprised by the resiliency of someone from the Greatest Generation who also served Michigan as a game warden.

One of my greatest joys at work is that as a wildlife biologist I regularly have interactions with conservation officers from across the state.

Some people may see a conservation officer with their badge and gun and assume “they are just an officer,” but I can tell you from experience it goes far beyond that.

Michigan conservation officers’ more than 130-year history is one of outstanding service to the state’s people and natural resources.

They act as the first line of defense in many emergency situations, are involved in their communities and exemplify what it means to be a law enforcement officer.

Outside of their work, I can’t begin to tell you the number of unique personalities I have met from the ranks of conservation officers: artists, musicians, trappers, hunters, anglers, foster parents, mentors and so many other examples.

Looking at the great men and women who wear the conservation officer badge each day in this state, I guess it should be no surprise to me that, way back when, Clarence Roberts designed a fly that is still in rotation today.

His Yellow Drake is one of the “must have” patterns for spring and summer trout fishing in Michigan, let alone other places around the globe – tied in various other ways based on region.

You can tie it from a small, size-16 sulfur, all the way up to the biggest hexagenia pattern. It is really a “do-all” pattern, that has stood the test of time.

I’d bet Roberts would find it incredible to know that his fly has been in tens of thousands of fly boxes – resulting in some of the finest brook and brown trout catches, creating countless memories for first-timers to seasoned anglers.

I’m sure, like many of the other Michigan conservation officers I have had the good fortune of meeting across the state, he would be the last person to pat himself on the back and instead probably would give credit to those around him.

A health condition forced Roberts to retire from the DNR in 1971, after just under 30 years of service as a game warden. He later moved to Florida, where he fished and tied flies for enjoyment.

He returned to Michigan a decade or so later. He died in 1984 at age 68. He is buried in Grayling in Crawford County.

Thinking about Roberts and his Yellow Drake, while stocking my fly boxes for the upcoming fly angler’s magical time of year, really got me thinking about this current COVID-19 situation that we find ourselves in and how much of an anxious and uncertain time it has been and will continue to be for a while.

I think of all the conservationists back in the 1930s, 40s and 50s and the many milestones they reached in the face of adversity and uncertain times.

How will I go forward in what my generation may consider our darkest hour and ensure natural resources are being taken care of?

How will I keep my mind right?

One day at a time and this too shall pass.

Find a river, take a few yellow bugs and think about what you can do to make sure clean, cold water and good habitat are there for generations to come. What part might you have in this?

Sit on a riverbank, read a book, slide into the water and cast a fly, get lost on a two-track road for a few hours this summer. Cross that songbird off your birdwatching life list, go after that fish you’ve been wanting to catch, reset those gears and look toward the future of good days to come.

Check out previous Showcasing the DNR stories in our archive at Michigan.gov/DNRStories. To subscribe to upcoming Showcasing articles, sign up for free email delivery at Michigan.gov/DNR.

Leave a Reply